Boulder monitor will stop referring cases both monitor and PSU call unfounded; panel objects and votes to seek outside counsel

November 13, 2025 | Boulder, Boulder County, Colorado

This article was created by AI summarizing key points discussed. AI makes mistakes, so for full details and context, please refer to the video of the full meeting. Please report any errors so we can fix them. Report an error »

BOULDER, Colo. — On Nov. 10, 2025, members of the Boulder Police Oversight Panel challenged the city’s independent police monitor after she described a new practice under which she and the police Professional Standards Unit (PSU) will jointly screen and close some complaint cases without referring them to the civilian panel for possible review.

Sherry, the city’s independent police monitor, told the panel she will “begin exercising discretion under the ordinance to not refer cases to the panel when PSU and I agree on unfounded or exonerated” classifications. She said the change is grounded in a 2023 general order that created a triage process to preserve limited oversight resources and reduce long delays for complainants and officers.

Panel members said the practice conflicts with the ordinance that established the oversight system and warned it weakens the panel’s independence and community oversight role. “I cannot, in good conscience, advise any member of my community to file a complaint right now because I don’t have faith in the system,” one panel co-chair told colleagues, summarizing the emotional response from several members.

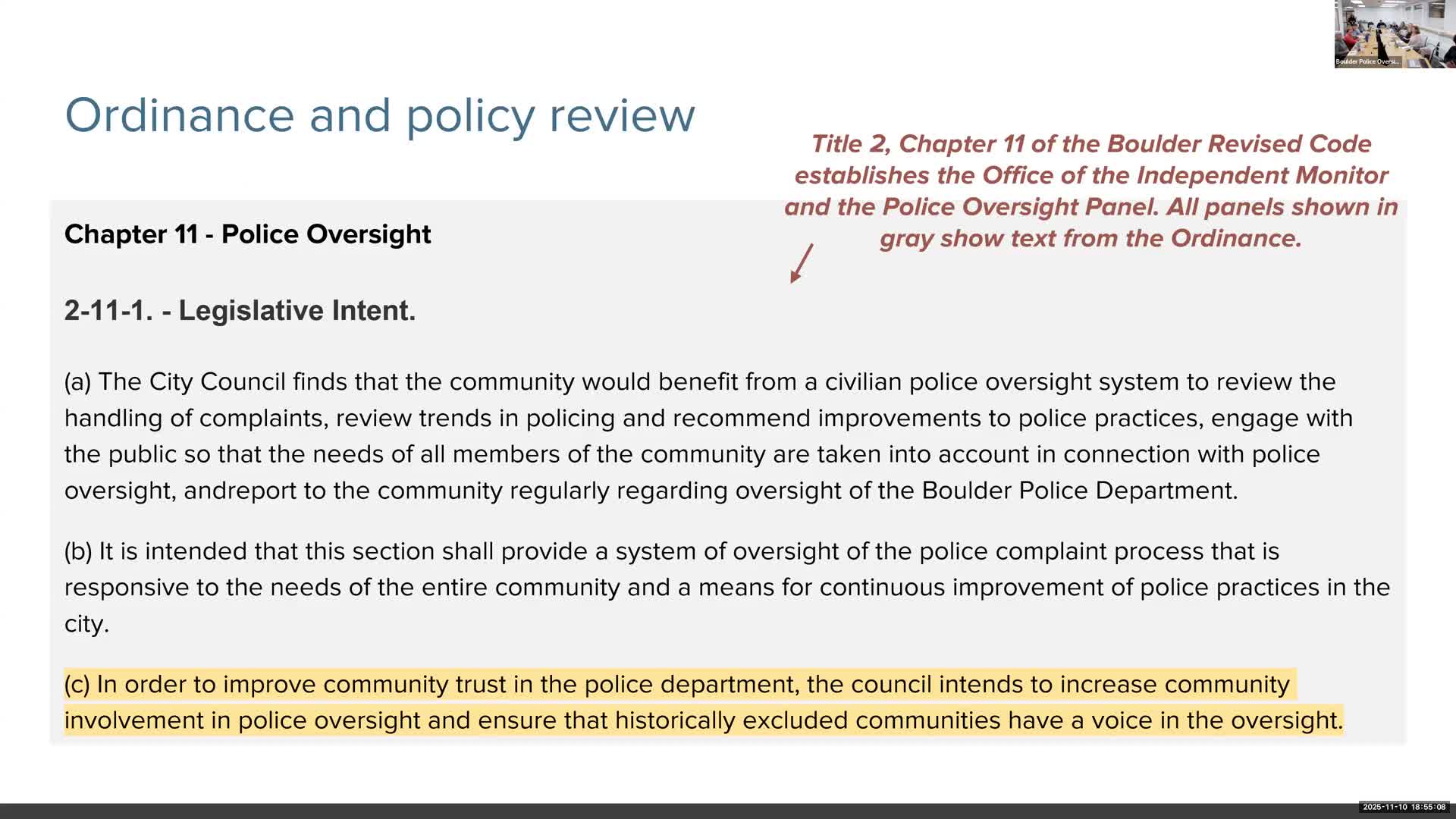

Why it matters: The panel was created after high-profile incidents and the ordinance repeatedly uses the term “complaint” and grants the panel access to complaint investigations. Panel members who took part in drafting the ordinance urged the city to preserve the panel’s ability to see all complaints and to provide written objections when the panel disagrees with police dispositions.

What the monitor and the city attorney said: Sherry defended the change as legal and operationally necessary, and said she will continue to provide confidential summaries and public reporting. Chris Reynolds, an attorney in the city attorney’s office assigned to oversight, told the panel the city attorney’s office views the terms “incident of potential police misconduct” and “complaint” as substantively aligned and that the monitor has discretion to refer incidents to the panel. He added the monitor remains obligated to report on all complaints to the panel for transparency.

Numbers and capacity: Panel staff presented case-tracking data for 2023–2025 showing shifts in how incidents are classified and a backlog that surged in 2024. The monitor estimated each full panel case review takes about five hours of her time (excluding police redaction work) and said the change could avoid a small number of full reviews — she cited roughly six cases in 2025 she had recommended closing that the panel then voted to review. Panel members disputed that modest time savings justified limiting panel access to complaints and suggested operational alternatives, including better use of video-redaction tools.

Motion and public response: Frustrated by what many described as a unilateral change in practice and an unclear legal interpretation, the panel voted to request that the city retain outside counsel to advise the panel on the ordinance and the monitor’s authority. The motion passed; one member (identified as Allen) was recorded as opposed. Community members who spoke during public comment urged the panel and the city to restore the panel’s access to complaints and to preserve civilian oversight as originally intended.

Next steps: Panel members asked the city attorney’s office and monitor to take the concerns back for further discussion and identified the city’s five-year ordinance review as a possible venue for clarifying language. The panel also requested independent counsel; the city must decide whether to retain outside counsel to advise the panel. The meeting was adjourned without any change to the policy at the hearing; panel members said they expect follow-up conversations with the monitor, the city attorney, and the city manager.

Sherry, the city’s independent police monitor, told the panel she will “begin exercising discretion under the ordinance to not refer cases to the panel when PSU and I agree on unfounded or exonerated” classifications. She said the change is grounded in a 2023 general order that created a triage process to preserve limited oversight resources and reduce long delays for complainants and officers.

Panel members said the practice conflicts with the ordinance that established the oversight system and warned it weakens the panel’s independence and community oversight role. “I cannot, in good conscience, advise any member of my community to file a complaint right now because I don’t have faith in the system,” one panel co-chair told colleagues, summarizing the emotional response from several members.

Why it matters: The panel was created after high-profile incidents and the ordinance repeatedly uses the term “complaint” and grants the panel access to complaint investigations. Panel members who took part in drafting the ordinance urged the city to preserve the panel’s ability to see all complaints and to provide written objections when the panel disagrees with police dispositions.

What the monitor and the city attorney said: Sherry defended the change as legal and operationally necessary, and said she will continue to provide confidential summaries and public reporting. Chris Reynolds, an attorney in the city attorney’s office assigned to oversight, told the panel the city attorney’s office views the terms “incident of potential police misconduct” and “complaint” as substantively aligned and that the monitor has discretion to refer incidents to the panel. He added the monitor remains obligated to report on all complaints to the panel for transparency.

Numbers and capacity: Panel staff presented case-tracking data for 2023–2025 showing shifts in how incidents are classified and a backlog that surged in 2024. The monitor estimated each full panel case review takes about five hours of her time (excluding police redaction work) and said the change could avoid a small number of full reviews — she cited roughly six cases in 2025 she had recommended closing that the panel then voted to review. Panel members disputed that modest time savings justified limiting panel access to complaints and suggested operational alternatives, including better use of video-redaction tools.

Motion and public response: Frustrated by what many described as a unilateral change in practice and an unclear legal interpretation, the panel voted to request that the city retain outside counsel to advise the panel on the ordinance and the monitor’s authority. The motion passed; one member (identified as Allen) was recorded as opposed. Community members who spoke during public comment urged the panel and the city to restore the panel’s access to complaints and to preserve civilian oversight as originally intended.

Next steps: Panel members asked the city attorney’s office and monitor to take the concerns back for further discussion and identified the city’s five-year ordinance review as a possible venue for clarifying language. The panel also requested independent counsel; the city must decide whether to retain outside counsel to advise the panel. The meeting was adjourned without any change to the policy at the hearing; panel members said they expect follow-up conversations with the monitor, the city attorney, and the city manager.

View the Full Meeting & All Its Details

This article offers just a summary. Unlock complete video, transcripts, and insights as a Founder Member.

✓

Watch full, unedited meeting videos

✓

Search every word spoken in unlimited transcripts

✓

AI summaries & real-time alerts (all government levels)

✓

Permanent access to expanding government content

30-day money-back guarantee